National Parks, State Forests

The Next Fire

Can we control fire with fire? Will more fuel reduction burning really save us and the bush we love? It’s time for a new approach, not failed remedies, says VNPA’s Phil Ingamells.

We learnt as children that fire is a good friend and a bad master.

And we’ve managed to tame fire in so many ways in our daily lives. But the relationship between fire, the Australian bush, and the people who live there is increasingly a fraught one.

Fire is undoubtedly master whenever the weather suits it, and the weather will be suiting fire more and more in the years ahead.

For many decades now the prime tool for fire management has been reducing the abundance of understory fuel, our shrubs and grasses, through planned burning and other means. It does seem to make sense – burning or clearing the fuel before a bushfire does – if you can actually do it.

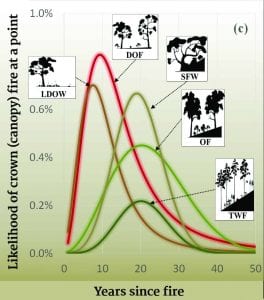

But in most ecosystems there is observed, as well as recorded and published, evidence that while a planned burn can reduce understory fuel for a year or three, in many or most ecosystems the post-fire growth of shrubs produces a significant increase in flammable shrubs over the next decade or more.

Let’s be clear about that. Fuel reduction burns can reduce the understory a lot for one year, and a bit for the next few years, but then they can actually increase the shrubby understory for many years. Eventually, over time (and this period varies), those shrubs gradually die off, and the understory becomes relatively low in fuel. Without more fire, it can stay that way for many years.

This ‘long-since-fire’ low fuel scenario is likely to be the explanation for many of the more open woodlands recorded by early European ‘explorers’. Frequently repeated Indigenous burning may well have contributed some of that open country, but not across the broad landscape.

Our understanding of how much this is true in different ecosystems, and under different burn and climate scenarios, would be very strong if fire managers systematically recorded the change in fuel levels in the years following fuel reduction burns. But that simple monitoring program hasn’t been happening.

It would be a serious enough omission in monitoring if this was only an issue of public safety, but it’s also an issue of protecting something like 100,000 native species. The fuel that threatens us is, at the same time, our invaluable, ancient, natural heritage.

Independent published research, however, such as that performed recently in the Australian Alps National Parks, makes this process clear (see diagram).

How effective has fuel reduction been?

Over the last decade, Victoria’s annual Fuel Management reports estimated a possible reduction in risk to life and property of up to 20 per cent maximum. But that would only be if all planned fuel reduction programs could be safely implemented.

That’s helpful but not much comfort, particularly when we know that in acute fire weather fuel-reduced areas actually do little to lessen the extent or severity of fire.

And though we’ve never managed to reduce fuel to any truly ‘safe’ level with planned burns, it somehow remains the chief fire management tool in the public’s mind, and also in the minds of many fire managers and politicians.

If we step back and look at things afresh, there are far more useful things we can do.

Protecting life

The over-riding priority for fire management is the protection of human life.

Unfortunately Forest Fire Victoria, in its planning, actually use buildings as a surrogate for human life. Why anyone would need such a weak proxy for such a critical and clear objective is a mystery; it’s possible to save buildings but lose lives, and possible to lose buildings while saving lives.

If we dump the surrogate, more effective life-saving options come into the picture.

Compulsory evacuation

While Victoria belatedly came close to compulsory evacuation in this summer’s fires, we still lack the necessary legal clout to achieve it. Fire managers should have the authority to evacuate homes, hospitals and even whole towns if necessary, and all regions should have well-developed evacuation strategies in advance of any fire season.

In the USA and Canada, compulsory evacuation is well established. In 2006, the 88,000 citizens of the Canadian town of Fort Murray were evacuated in the face of a several hundred-kilometre fire front. The town was lost, but everyone lived.

Private bushfire bunkers

The Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission found that half of the people who relied on private bunkers during the Black Saturday fires survived, but half tragically perished in them. The Commission put out an urgent interim report asking for an approved Australian standard design for private shelters, and that standard was published before the Commission’s final report.

However, this critical information has never been communicated to Victorians, and there has been no support for people wanting to install approved shelters. They should, at least, be compulsory for any new building in a high fire-prone area.

These are among a few very employable strategies that can effectively contribute to safety.

But there is one seriously big investment that might radically change fire management in the state.

Rapid attack capability

Fires ravaged Tasmania in 2016, burning the previously unburnable high tablelands and incinerating Pencil Pines that had been unburnt for a thousand or more years. But the Tasmanian government was poorly equipped to handle fire in these remote areas, and had to rely on aircraft coming across Bass Strait from Victoria. They arrived far too late to avoid disaster.

Around Melbourne however, faced with the prospect of catastrophic loss of life in the Dandenongs, Warrandyte or the Mornington Peninsula, we now have the capacity to get three aircraft to an ignition point within 10–15 minutes of notification of a fire.

Our aerial attack capacity has increased steadily since 2009’s Black Saturday fires, but rolling out a truly effective aerial point of ignition capacity across Victoria would be expensive, possibly a billion dollars or more. However Black Saturday cost Victoria over $4 billion, and 173 lives, and this summer’s fires have been more expensive.

This is a highly technological solution, but in the face of climate change, it may be the only effective way to seriously reduce the rate of fire in the landscape. We won’t stop every fire, but we should set about establishing a far greater level of control than we currently have. There are other ways to help control ignitions, such as burying power lines, a recommendation of the Royal Commission and later rejected by our state government, or encouraging local power generation (which is also good for the climate). And better strategies to control arson could also help.

Investing seriously in ignition control could have many benefits, increasing:

- public safety

- public health

- protection of infrastructure

- protection for agriculture

- protection for tourism

- viability for insurance companies

- reduced carbon emissions

- And … long-term benefits for biodiversity

That has to look like a good return on such a solid investment.

If we reduce the frequency of severe fire, we should be able to decrease impacts on both lives, infrastructure and the environment. And in the long-term, though this might be difficult under climate change, we could potentially decrease the flammability of much of the landscape.

Fuel reduction will always have a place in managing bushfires, especially when it is performed strategically close to assets in need of protection.

But increasing management burns across the landscape won’t be the panacea many are claiming, even if it were possible to achieve the task.