Protected Magazine

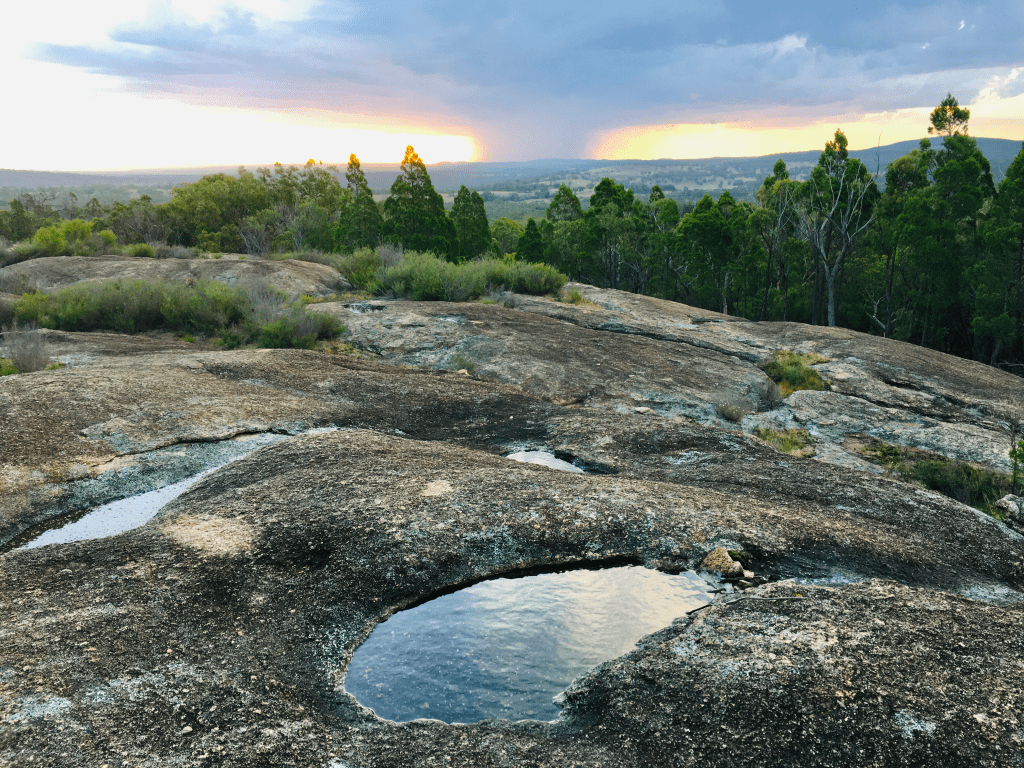

Tumbledown Nature Refuge: A Day of Forest Life

This morning I woke to the sound of five kookaburras chuckling uproariously at the slow ascent of sunrise from one of their many precarious perches at the top of a large, old growth Eucalyptus youmannii (Youman’s Stringybark).

Every morning it’s the same. About 15 minutes after the first announcement they begin all over again, followed by the slightly lugubrious calls of white eared honeyeaters and thornbills, I imagine them saying “Whaaaat, really, you mean there’s a whole new day in front of me? Well, better get on with it, I spose.” And that’s what we all do.

My name is Jayn. My home is Tumbledown Nature Refuge in the high country west of Stanthorpe, Queensland.

I live on and care for over 80 hectares of pristine granite heath and endangered woodland ecosystems on two adjacent nature refuge properties. I am dedicated to the preservation of all forest ecosystems and I am presently writing a book aimed at explaining as simply as possible, some of the approaches that we can take towards a ‘return’ to forest consciousness and practical activism, no matter where we live or work.

Income and many of the resources of my lifestyle come from the forest. I live by a code of resilient, less moneyed, reductive lifestyle and as close to the raw truth of low impact sustainability as I can. I am a forest keeper.

‘Keeper’ is appropriate since inferred in its meaning is the great responsibility of ‘keeping order’ or in other words, conservation of the forest resource in the sense that he/she, the keeper, is in service to the forest ecosystem and all of its inhabitants in a mutually beneficial relationship with forest. A forest keeper embodies all of the occupational skills of forest workers, biologists, rangers, gardeners and arborists, as well as in my case, a good deal of pragmatism. The forest keeper of old was an important part of a resilient forest economy with many responsibilities including policing poaching activity, seasonally managing harvesting of forest resources, managing teams of people who lived and worked in the forest, carrying out feral animal control and maintaining borders, roads and common lands. In a contemporary context, I also carry out similar daily tasks.

As a practitioner of the science of forest keeping, I carry out some important work and research in the complex, biodiverse heathy woodland ecosystem I call home. I utilise techniques of thinning, tree surgery, soil nurture, feral animal control and cultural burning, adjuncts to encompassing life methodologies practised for the good of the planet and all of its living creatures.

I’ve evolved into ‘tree-ness’ over a lifetime beginning in early childhood by drawing and identifying trees almost obsessively and growing from seed, and establishing, over 20 000 rainforest and sclerophyll trees on my first property which I purchased in my late teens.

Forest keeping is a vital part of ‘living in the forest’ and by that I mean, living in a way that means the forest and a person’s lifestyle are inseparable and each entity is necessary for the other.

I have worked alongside traditional owners who are the fire, soil and water keepers of their cultures. I’ve also learned a lot from twenty years of wandering over thousands of hectares of almost pristine heathy woodland, bearing witness to its slow degradation and disintegration without the remedial and perpetuating influence of forest keeping techniques and traditional First Nations ‘cultural burning’. I wonder often what it must have been like before white men altered the vistas forever by transplanting their European values into the oldest landscape on the planet, something we continue to do.

Tumbledown and the surrounding country encompass a wide range of ecosystem microcosms from flooding arid swampland, riparian zones, sedgelands, grasslands and heathy open woodland to the granite domes that support many rare and endangered species of orchids, heaths and fauna such as the Border Thick-tailed gecko, glossy black cockatoos and heathwrens.

As Nature refuge occupants, our joint vision for the future is to conserve these precious endangered heathy woodland ecosystems through a combination of methodologies encompassing tree thinning regimes, particularly endemic but invasive Callitris endlicheri, conservation and preservation of large diameter, old growth eucalyptus species, appropriate cool (cultural) burning methods in small compartment mosaics and involvement and education at community level with local First Nation traditional owners and other property stakeholders willing to trial such methodologies on their own places and on public lands.

Tumbledown has been undergoing a slow transformation over a period of about 10 years of ministering to the senescent and degrading status of the forest biome. The results of application of culturally appropriate fire and conservative thinning of vegetation are promising great benefits for comprehensive ecosystem health as well as fire load reduction and a lesser danger of hot, destructive wildfire. At community level, education programmes and demonstration of the techniques that we use in collaboration with local First Nation rangers, are inspiring many others on the land to follow suit.

Long term observation of changes at Tumbledown, points towards population diversity declines of native animals. Birds may be the harbingers of that horrible reality. Anecdotally, declines in insect populations and fruiting, seed and nectar bearing plants in marginal zones like Tumbledown may already be exposing this problem.

From the house, I have a great view of the bush garden surrounds and the pond, where live a multitude of dragonflies, wasps, visiting crimson rosellas, eastern spinebills and many other birds that frequent this tiny watery oasis in a normally arid environment. At night I leave apple and carrot scraps out for a little swamp wallaby that has an injured foot, perhaps healed now, but crippling it permanently. Here in its natural wilderness, the injured wallaby is relatively safe, has plenty to eat and it seems right to let it graze undisturbed.

I benefit from living with the wild creatures that hop, fly, flutter, slink, crawl, scuttle and volplane right past me as I walk along the many pathways and animal trails of this extraordinary 100 acres of ‘wildergarden’. The forest is life, not only for the animals but as a source of some of my income, of food, entertainments and the renewable resources to make things that I use or that I sell. Blessedly, the forest brings a peaceful quiet rhythm to life on this nature refuge.

Each morning live catch traps I use to catch feral cats and foxes have to be checked. The feral animals are dispatched humanely. All the natives are released unharmed, usually full of whatever delicious treats I have set the traps with. Except for mice and rats that are used as bait, the dead are buried with respect beneath the lime and olive trees in the orchard. They are wild animals too.

A small chainsaw, full PPE and maintenance tools in a bucket and a sharp hand axe is all I need to do forest work. I start with a few hours of thinning of whipstick infestations of Callitris endlicheri (Black Cypress) and stunted eucalyptus saplings.

Thinning the forest before it can be burned, is physically demanding work, so I work in small, manageable compartments of about 100 – 300 sqm at a time. I carry out forest work with the principle of leaving no or only minimal trace of having been there. This approach also makes the cool burns much safer to carry out when conditions for burning are appropriate. The pathways are also firebreaks that follow natural watercourses and well worn animal trails. Animals always take the easiest path and the forest gently instructs us about where we can tread lightly, if we care to listen and observe.

Often there is a need to cut out up to 70% of tree stems, mostly whipstick and overcrowded callitris which will eventually dominate the forests of the Granite Belt. This will lead to hot fire and even more regrowth and less biodiversity.

I remove most of the trees surrounding an old growth eucalyptus tree, freeing its wide, tip sensitive canopy, and opening up the struggling understory of heath, native grasses and herbs to sunlight.Trees that were thinned around, near the homestead a decade ago, survived the drought with healthy canopies on this dry, bony ridge, while trees that had not had similar treatment died in droves in every other part of the forest.

Clearing up the mass of tree heads, firewood and cordwood sections is by far the most arduous and time consuming work, but is essential for cool burning later on during the winter months. The wild animals don’t seem to object at all, evident in an increase in scats and footprints and advantageous wear on the tracks, as well as in the chewed new growth. The benefit goes both ways, you see.

Everywhere around us all, nature in all its incredible diversity and resilience can be observed. I walk for many kilometres over a fascinating wild landscape of thousands of hectares in the immediate environs and in the nearby Amiens State Forest. There are so many things happening to trees and in and under them as well. This forest is certainly alive. Life on a Nature Refuge never stands still. Well, not unless you are a granite monolith.